“We need to re-write the narratives about migrants; we need to tell refugee stories of pride, resilience, innovation, courage, integrity, intelligence, and we need to tell the stories of refugees contributing to the economy,” Dr. Anne Dolan told a largely student population at Mary Immaculate College on February 23, 2016.

Open Dialogue Series fifth forum addressing issues Ireland is facing

A Lecturer in Primary Geography at the university, Dr. Dolan said “we, as teachers, need to tell the other side of the story against some media narratives, [and] children need to hear these alternatives because the media messages are quite dangerous.”

The Global Peace Foundation Ireland hosted the forum, “Where Are We Now? Exploring the Ongoing Response to the Refugee Crisis,” which focused on encouraging a shift away from negative immigrant narratives that are dominating the media to more positive stories of immigrant experiences.

The forum was the fifth of the Open Dialogue Series—a program of the Global Peace Foundation Ireland, public intellectuals and Mary Immaculate College focusing on finding solutions to a variety of issues facing Ireland today—and specifically addressed the current refugee influx affecting Europe.

Other presenters also described the Irish response as “not very welcoming.” Leonie Kerins, Director of the Limerick-based migrant organisation Doras Luimni, noted that Ireland is the 11th richest country in the world according to its Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita. “How can we not accommodate asylum seekers and especially children?” he asked.

Kerins said there are about 500 asylum seekers living in Limerick’s four Direct Provision centers. The biggest unit hosts 250 migrants, 50 of whom are children and most of whom were born in Ireland [if they are born there they aren’t migrants]. Kerins warned that refugees at the centers face challenges including mental health, protracted isolation, reduced self-esteem, idleness and internal conflicts.

Adding that new Ireland asylum seekers are likely to face the same problems as those already living there, Kerins called on the country’s Justice Department to replace the centers with a rental accommodation system that would offer better social support, recreational activities especially for children, community interaction, and better means to learn the English language.

Migrants from different backgrounds also attended the event, including a Syrian woman who migrated to Ireland in 1999. She described her country before the war as “the most beautiful country with every city being unique, which was proud of its heritage,” and with “all 32 different ethnicities living in a peaceful setting.”

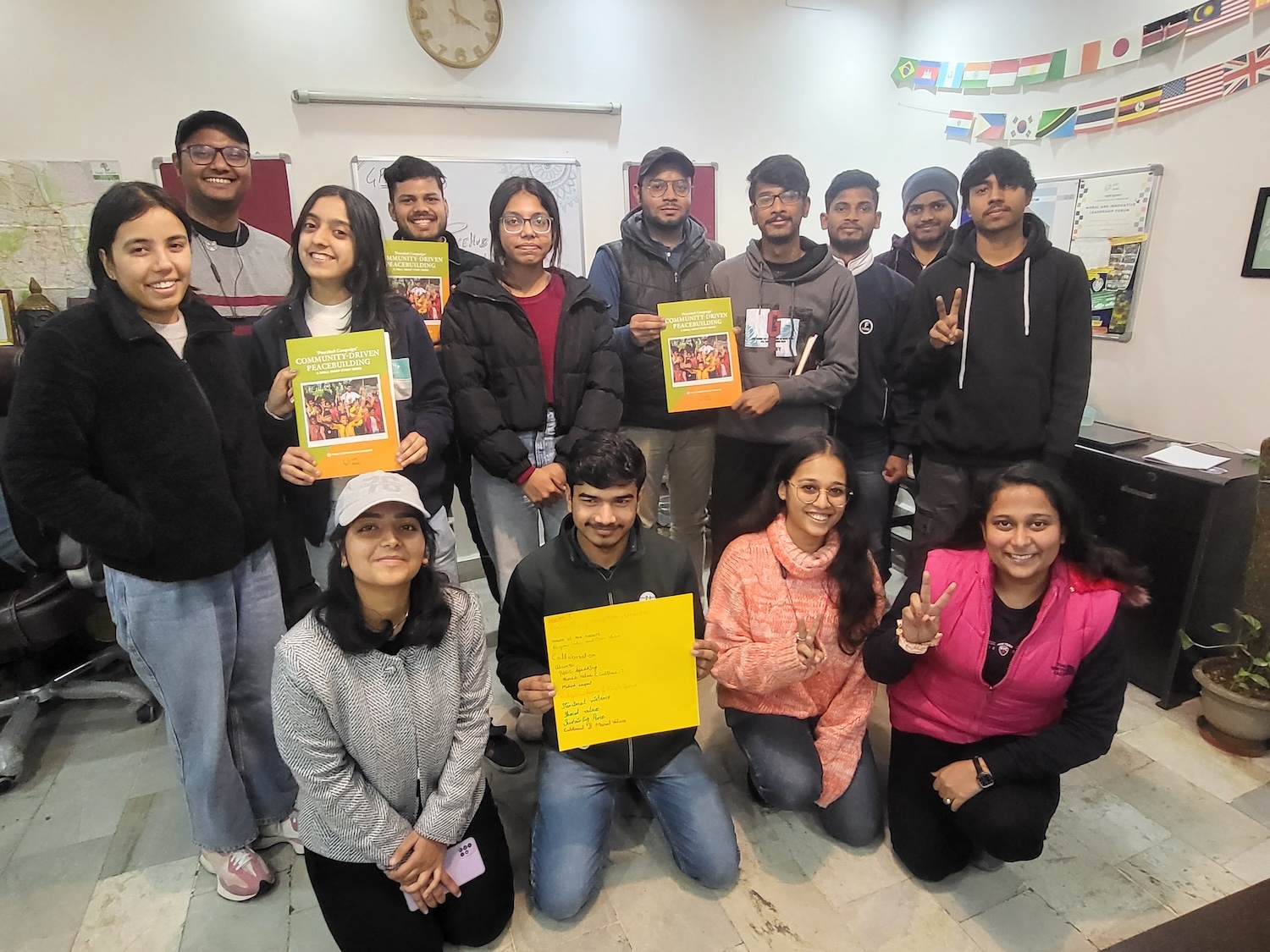

A speaker addresses the largely student population.

Now studying to become a psychotherapist, she said she had become disconnected from her country and endured a lot of difficulties when she first came to join her husband in Ireland. “I spent the first six months by myself because my husband had to be at work. I spoke little or no English and it was very hard on me.”

Brighid Golden, Coordinator of Development and Intercultural Education project at the university and moderator of the event said, “Last year, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees reported that almost 60 million people had been forcibly displaced by the end of 2014.” At that time there were about 4,280 people in DP centers awaiting results of their asylum cases.

Over the past few years, Ireland has come under intense criticism for its low rate of granting refugee status to asylum seekers and for rejecting and deferring asylum decisions in comparison to other members of the European Union such as, Norway, Bulgaria and the United Kingdom.