April in Rwanda brings back painful memories for some. In 100 days nearly 800,000 Rwandans were killed. The difference between the killed and the killers was a marginal divide, “mostly artificial, a leftover from history,” wrote Paul Rusesabagina, a man attributed to the survival of more than 1,200 people who sought protection in Hotel Millie Collines, of which he was manager during the killings.

The harrowing 100 days began on April 6, 1994, when news of Hutu President Habyarimana’s plane crash sparked hate messages over radio waves. That night the killings began. By the next day 1,000 Tutsis were already dead, but it was just the beginning. Neighbors killed neighbors, family turned on family. Schools and churches where people sough sanctuary became mass graves.

As the world, including the United Nations and developing nations like the United States, Great Britain, and former trustee of Rwanda, Belgium, struggled to decide how to respond, the killings continued.

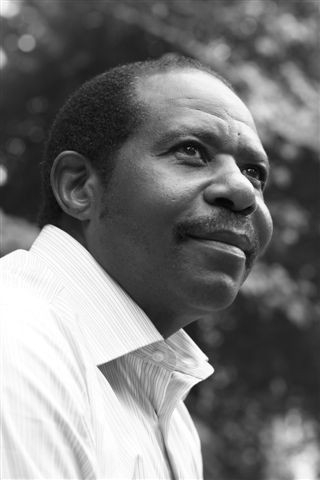

Paul Rusesabagina

Yet, even in moments such hellish horror, the best of humanity shines and faith is born out of the ashes of destruction. Among the countless heroes who stepped up, defying orders, stomaching fear, and “facing history” to “do what is right” is Paul Rusesabagina. He is humble about his feat, recognizing that there were many others. He said, if a Tutsi survived, a Hutu risked their life, sometimes lost their life to protect that Tutsi.

In his interview with NPR Talk of the Nation in 2006, Mr. Rusesabagina was asked why he decided to protect his neighbors and the people who came to seek refuge at the hotel. His responded:

“I call my conscience my advisor. My advisor was telling me that listen, do not leave these people behind. If you do, and they are killed, you will never be a free man. You will be a prisoner of yourself. You will never eat and feel satisfied. You will never drink and feel satisfied. Don’t leave them behind. This is an opportunity.”

As the world remembers the tragedy that swept through in April, Rwandans remind the world that theirs is not a unique story, nor it is it one of the past. In parts of the world brothers continue to kill brothers, neighbors kill neighbors. The thin line between life and death is often so hard to discern. Such stories reinforce the need for humanity to find a common bond that can shatter the divides along which hatred, oppression, and violence fester. And that we need to stand up for that common bond, even if it is extremely inconvenient and sometimes dangerous.

A recent example of progress is the past Kenyan Presidential Elections. The world held its breath as the polls opened, worried of a repeat of the bloodshed of 2007. Yet, the media and social media remained mostly free of hate speech that burned hotly during the last election; and through polling machinery glitches, long lines, and election fraud claims, Kenyans pushed for one verdict, Amani. As a nation, grass roots and high level they willingly reached across their differences to affirm that they dream as one nation. The Global Peace Festival was recognized as a key contributor to the peaceful elections.