Korea experts in Moscow, London, Stockholm, Seoul, New York, and Washington discussed new opportunities for resolving the decades-long challenges of bringing peace, reunification and denuclearization to the Korean peninsula and Northeast Asia during a virtual roundtable on June 2, 2020.

Highlighting European and Russian geopolitical perspectives, the forum advanced an earlier round of virtual discussions on May 26, which examining Mongolian and Japanese views on security and denuclearization in Northeast Asia.

Welcoming participants, Co-President of Action for Korea United Inteck Seo said that despite the heightened challenge of COVID 19 and deteriorating U.S.- China relations, “we need to make our destiny clear. A vision of a unified Korea should be accepted by neighboring nations.”

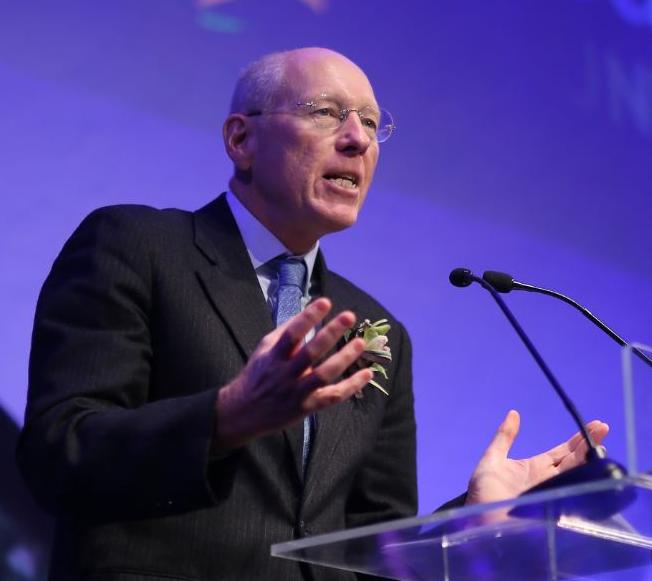

In opening remarks, Dr. William J. Parker, CEO and President of the EastWest Institute, credited the efforts of the Global Peace Foundation to bring international focus to unification as a means to resolve the security threat of the divided peninsula. “Your efforts, your comprehensive and strategic vision, quite frankly, is the most thoughtful approach I have seen, and I have been working on this for 25 years. GPF has it right; security, governance and economics are the key three steps. My strong belief that issues like Korea, Venezuela, Syria, and the list goes on, won’t be resolved until a much bigger issue— relations between the U.S. and Russia—are resolved first.”

Russian perspectives

Dr. Alexander Zhebin, Director of the Center for Korean Studies at the Institute of Far Eastern Studies in Moscow, said that Russia generally welcomes all moves by two Korean states aimed at relaxation of tension and promoting inter-Korean cooperation. “Moscow hopes that inter-Korean reconciliation will remove a threat of military conflict right next to her Eastern border,” Dr. Zhebin said, “and secondly, promote a more favorable environment for both development of Russia’s bilateral economic ties with two Korean states as well as for implementation of multilateral economic projects.”

Dr. Alexander Zhebin speaks on Korean reunification at a forum in Washington sponsored by the Global Peace Foundation and the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

At the same time, he cautioned that Russia (and China) would hardly welcome a unified Korea, a country with 75-million population, as a new neighbor under the prevailing influence of the U.S.A., particularly with U.S. troops on its territory.

“The fundamental, key issue which any peace process in Northeast Asia should work to resolve is defining an acceptable place for the unified Korea for all ‘big countries’ in the future regional security system,” Zhebin said. “A neutral, unified Korea with international guarantees from the U.S.A. China, Russia and Japan may be the most acceptable option to all those concerned and interested in an early and peaceful Korean settlement.

“Members of the Big Four (China, Russia, the U.S.A. and Japan) should give formal guarantees of a unified Korea’s neutral status. This status could be supported and reinforced by the UN Security Council, which can adopt a special resolution to that effect. It is high time for Korea to take destiny in own hands,” he concluded.

European views

John Everard, former UK Ambassador to Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, described European Union attitudes toward reunification as “firmly agnostic,” saying the EU has no position on unification, and European engagement with North Korea is shrinking.

Amb. John Everard addresses the Global Peace Convention in Seoul in 2019.

“In the heady days at the turn of the century the European Union was deeply engaged,” Everard said; “there were cultural exchanges, an annual dialogue and significant amounts of money flowing into North Korea. But experience has scarred the EU. When President Moon toured European capitals in 2018 seeking support for his reunification plan, he didn’t succeed; statements were very cautious, mostly about denuclearization, which was considered a much higher priority.

“If North Korea were to get serious about unification issues,” Everard said, “the EU would be prepared to use its good offices and even its resources to move the process forward.

“By any measure the European Union remains the biggest Western presence in North Korea. Nearly every EU member state has diplomatic relations with North Korea and, indeed, North Korea uses EU embassies as a ‘sounding board’ about what the West in general thinks, and specifically the UK embassy as a kind of a surrogate U.S. embassy. This alone would probably engage the European Union in any meaningful movement toward unification, should such a process ever take off.”

Toward unification and denuclearization

Dr. Tarja Cronberg, a Distinguished Associate Fellow with the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, reminded the roundtable that in 1992 North Korea and South Korea had a joint declaration of nuclear weapons-free zone covering the two countries, including discussions about control and verification. “The U.S. was not involved and had nuclear weapons in South Korea at the time,” she said, “so one questions whether such an approach would have any value in today’s environment as a precondition for unification.”

Dr. Cronberg said that an idea circulating in the international community of a nuclear weapons-free zone covering South Korea, North Korea and Japan, with security guarantees from the United States, China and Russia, could provide a meaningful approach. She said that the withdrawal of the United States from the Iranian nuclear arms deal in 2018 and U.S. efforts to extend a UN-imposed arms embargo against Iran highlighted the difficulties of nuclear diplomacy in the current environment.

“A neutral, unified Korea with international guarantees from the U.S.A. China, Russia and Japan may be the most acceptable option to all those concerned and interested in an early and peaceful Korean settlement.” —Dr. Alexander Zhebin

Sustained Dialogue Institute President Rev. Mark Farr turned the discussion toward the integrity of the diplomatic process. He said the Dartmouth Conference, the longest continuous bilateral dialogue between American and Soviet (now Russian) representatives, has some relevance. Established in 1960, the conference “has never given a public paper or taken a position on anything,” Farr said. “Why is that relevant? We do not take a position on unification of Korea but we believe that it is in the sustained conversation, the quality of the conversation, that solutions may emerge. We want to say simply, ‘we must talk.’ Now that has been decreasing in recent years between the U.S. and the Russian Federation.”

Farr said that recent summits surrounding the Korean peninsula were not in his view authentic dialogue, but “leaders intent on making statements,” and unhindered, sustained, private dialogue could achieve more.

“The importance of listening and believing people when they say things, even those who feel repressed—and I would include the Russian Federation, who feel that this could be a threat on their southern flank—need to be heard and taken seriously. If the U.S. doesn’t take those interests into account, it will not result in a sustainable solution.”

The highest level, he said, was on the cultural level, “the desire of peoples who have been separated to come together. And in the long term, that is almost unstoppable.”

From left: Dr. Tarja Cronberg, Rev. Mark Farr, and Dr. Vladimir Ivanov presented perspectives on reunifiction during the virtual forum.

Vladimir Ivanov, Director of the Russia and United States Program at the EastWest Institute Moscow Office, said he didn’t see critical interests that would lead to imminent change on the Korean peninsula. Calling unification “a remote dream, very inspiring,” he conceded that “no one would have dreamed of unification of Germany or the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1985 or 86, but it did happen against the background of very significant changes in political systems.”

Most of major players, he said, would prefer the status quo, with gradual rapprochement and demilitarization of the Korean peninsula.

Ivanov suggested that the development of new technologies, including hypersonic weapons and cyber capabilities and that can interfere with command and control of weaponry, may make nuclear strength less definitive and more risky than during the Cold War and bipolar era when the U.S. and Soviet Union were relying on nuclear strength not only as war instrument but as a containment strategy.

“With higher risks come the need for more negotiation between critical players,” Ivanov said. As an example, he cited a new EastWest Institute report on terrorism and the peace process in Afghanistan, with an analysis of U.S. and Russian interests in the process. “Despite competition on the global stage, the two countries were close, if not partners and allies, and were in alignment in their positions,” he said.

Noting parallels in Northeast Asia, Ivanov said the EastWest Institute would be happy to support the U.S. initiative to engage China in arms control talks with Russia, and to advance discussions on denuclearization and reunification on the Korean peninsula.

The roundtable was hosted by the International Advisory Council on Korean Unification and NE Asia Peace and Development, Global Peace Foundation, EastWest Institute, and Action for Korea United.