To some, the reunification of the Korean peninsula may seem like a slow, incremental process that will occur in the distant future. But to others, particularly those that have experienced living in North Korea—deprived of fundamental human rights and freedoms—Korean reunification should happen today. Rather it should have happened decades ago.

The One Korea Global Campaign is advancing the dream of a free, unified Korea where all Koreans may live with dignity. And part of that process is bringing light to one of the greatest human rights issues of our time. Unsurprisingly, some of the most passionate advocates for One Korea are North Korean defectors. Their harrowing stories remind us that many families are still separated and that a unified nation that upholds fundamental human rights and freedoms for all Koreans is something we should all work toward urgently.

The following article was first published on Action for Korea United (AKU) Japan

The human rights issue in North Korea goes beyond the issue of compulsory camps and expands to include North Korea’s abduction of Japanese citizens whose whereabouts and safety are currently unknown. In 2002, representatives of Japan met with Kim Jong-Il in Pyongyang who in turn recognized the abduction of Japanese citizens and allowed five abductees to return to Japan.

But that’s it. There has been no further development for the resolution of this issue since then. The Japanese government regards this issue as a serious problem that threatens Japanese sovereignty and the lives and safety of Japanese citizens. Japan makes it a principle not to accept negotiations for normalization of diplomatic relations with North Korea unless the nation addresses this abduction issue first.

While a certain level of awareness on the abduction issue still exists in Japan, a bigger problem is hidden behind it, namely the project “Diasporic Returns to the Ethnic Homeland of North Korea.” From 1959-1984, an effort was made to return members of the Korean diaspora and their families living in Japan to the homeland. As many as 93,940 people, Koreans and their families living in Japan at that time, went to North Korea but most were never allowed to go back to Japan. All the while their freedoms and human rights were severely restricted and trampled on.

But they were not all Koreans. This group included 1,831 Japanese wives and their families who have Japanese nationalities for a total of 6,839 Japanese people. Some of them were sent to compulsory camps as political prisoners on the grounds that they lacked loyalty to North Korea and its leaders, while others were discriminated against as those who had experienced capitalism in Japan.

Kang Chol-hwan’s Story

Kang Chol-Hwan

Kang Chol-hwan managed to escape from North Korea in 1992 after having been imprisoned with his grandparents, father, uncle, and his sister in Yodok political concentration camps for ten years. His grandfather, who had lived in Kyoto, made a lot of contributions to “Chongryon,” the General Association of Korean Residents in Japan; and as such, his family was one of the richer families in the Korean diaspora in Japan.

In 1963, his grandparents and parents moved to Pyongyang through the project of Diasporic Returns, and contributed a large amount of money that they had earned in Japan to the North Korean Labor Party. But his grandfather was arrested on the grounds that he had not attended party conventions and meetings. As a result, his grandfather and family members were sent to a concentration camp based on guilt by association.

Kang Chol-hwan, who was born when his parents lived in Pyongyang, was sent to a concentration camp when he was just nine years old.

In his writings “The Aquariums of Pyongyang” and “Escape from North Korea (co-author: An-Hyuk),” he witnessed many victims from the project of Diasporic Returns, namely Koreans who had lived in Japan and their wives, living in concentration camps. He also heard from his grandmother that ten Japanese wives had died of diseases such as dysentery in concentration camps partly because they were more susceptible to the illness than Koreans.

An Unrecognizable Homeland

Ahn Myung-chul, who worked in a political concentration camp as a security guard member, heard whip sounds from security guards lashing and torturing a Korean lady who had returned to North Korea from Japan. She was imprisoned in a camp known as the “North Korea Concentration Camp of Despair.” With repeated whip sounds resonating, the lady shouted in Korean at the intimidating security guards:

“I came here to my homeland since the Supreme Leader had called us to come. But what on earth is my homeland? How can it be my homeland if I am being tortured by you just because I came back from Japan?

“Alas, why did I come to North Korea from Japan? How was I not able to foresee such a thing before I came here? Why did I come here with my husband and bring my children? I just came here because I thought this place was my hometown but why do you treat us as spies?

“Damn it all. Bring my family back to Japan. Otherwise, just kill us all.”

She shouted and suddenly became silent.

Two Nations and Two ideologies

Why was the project of “Diasporic Returns” conducted so long?

From August 15th, 1945 to the end of March 1946, right after Korea was released from Japan, about 1.4 million out of the 2 million diasporic Koreans in Japan went back to the southern part of the Korean peninsula, which is now South Korea. Only 361 people returned to North Korea in 1947. At that time, about 514,000 out of about 647,000 members of the Korean diaspora in Japan, wished to return to the Korean peninsula. On the other hand, only 10,000 or fewer wished to return to the northern part of the peninsula.

From August 15th, 1945 to the end of March 1946, right after Korea was released from Japan, about 1.4 million out of the 2 million diasporic Koreans in Japan went back to the southern part of the Korean peninsula, which is now South Korea. Only 361 people returned to North Korea in 1947. At that time, about 514,000 out of about 647,000 members of the Korean diaspora in Japan, wished to return to the Korean peninsula. On the other hand, only 10,000 or fewer wished to return to the northern part of the peninsula.

After the liberation from Japanese colonial rule, the conflict between the United States and the Soviet Union brought about the divide and conquer system between the North and South, but it ended in 1948 with the establishment of two nations with differing ideologies: South Korea and North Korea. The differences between the two countries had great impact on the Korean diaspora in Japan as well. Eventually, two unions in Japan coexisted: the Korean Residents Union in Japan, and the General Association of Korean Residents in Japan, with ties to South and North Korea respectively.

In April 1948, right before the establishment of the Republic of Korea (ROK), residents in Jeju island who had opposed the division of the peninsula, conducted an armed uprising in opposition for the separate election in the southern part of Korea. Security troops from the mainland of Korea suppressed and killed many residents. As a result, many islanders fled to Japan, creating a new community of Koreans in Japan.

The Korean War, that occurred from 1950 to 1953, ended the repatriation movement. In 1952 South Korean President Syngman Rhee established “The Syngman Rhee Line,” known in Korea as the “Peace Line,” in which the South Korean military captured many Japanese fishing boats. In some cases, the military shot ship crew members to death. So, Japan and South Korea were in a growing state of excessive tension.

At that time, Japan had entered the first period of high economic growth but only had a lean budget. Members of the Korean diaspora in Japan had difficulties in finding jobs because of discrimination, which increased their unemployment rate and their rate of receiving social welfare. By the end of 1955, the rate of Koreans receiving social welfare in Japan was 24% which was more than ten times that of Japanese people. But due to the budget shortfall, the Japanese government cut public assistance recipients by 40% over the following year and a half, which led to even worse economic impoverishment of Koreans living in Japan.

Broken Promises from Paradise on Earth

South Korea could not receive any more Koreans from Japans since it was recovering from the Korean War and was in a period of reconstruction. On the other hand, Kim Il-sung announced that North Korea was ready to welcome Koreans back from Japan and that every provision would be guaranteed to them. The General Association of Korean Residents in Japan, an organization with ties to North Korea, was established in Japan in May 1955. North Korea started the “Five-Year People Planned Economy Project” known as the “Chollima Movement” in 1957.

Subsequently, the General Association of Korean Residents in Japan upheld the goal of “Advancement of Diasporic Returns,” thus establishing a stable position for itself in Japan. The General Association of Korean Residents in Japan praised North Korea as a “Paradise on Earth,” and lied to promote the Diasporic Returns movement:

“We are ready to sufficiently provide all physical provisions such as houses, food, and other necessities for living.

“All medical costs are free.

“Koreans in the diaspora will have many job opportunities in their fields of choice.

“Koreans in the diaspora can go back to Japan in three years if they so wish.”

The Japanese media also supported the false propaganda at that time.

South Korea kept objecting to Diasporic Returns to North Korea because of the fear that North Korea would take advantage of the fact that diasporic Koreans in Japan adhered to North Korea instead of South Korea and use it as false advertising. South Korea also feared that communists might use Japan as a transit point to go back and forth between South and North Korea.

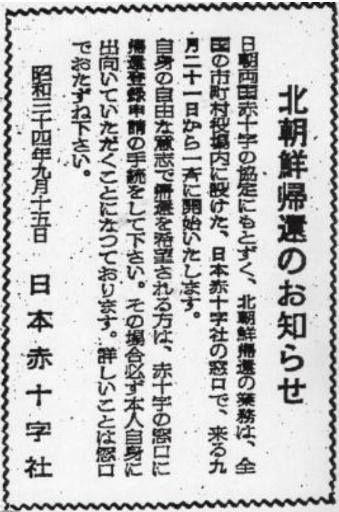

The Japanese government received backlash from South Korea for this and also had difficulties in sending Koreans, who had no passports, to North Korea, a nation with which Japan lacked diplomatic relations. For these reasons, the Japanese government concluded that it would be difficult to go forward with the project between the two governments, and therefore allowed the Japanese Red Cross Society from the private sector to negotiate with the Korean Red Cross Society over the Diasporic Returns project. Furthermore, the Japanese government anticipated the involvement of the International Committee for the Red Cross (ICRC) and endeavored to supervise to ensure that returning to North Korea was based on the free will of diasporic Koreans, and that North Korea could not take political advantage of the Diasporic Returns project.

The Japanese government received backlash from South Korea for this and also had difficulties in sending Koreans, who had no passports, to North Korea, a nation with which Japan lacked diplomatic relations. For these reasons, the Japanese government concluded that it would be difficult to go forward with the project between the two governments, and therefore allowed the Japanese Red Cross Society from the private sector to negotiate with the Korean Red Cross Society over the Diasporic Returns project. Furthermore, the Japanese government anticipated the involvement of the International Committee for the Red Cross (ICRC) and endeavored to supervise to ensure that returning to North Korea was based on the free will of diasporic Koreans, and that North Korea could not take political advantage of the Diasporic Returns project.

On August 13, 1958, the Red Cross Agreement between Japan and Korea on Diasporic Returns of Koreans in Japan was finally signed. It clearly stated that North Korea was responsible for preparing ships to North Korea and would pay their travel costs. This agreement could not, however, state in concrete terms how ICRC was to be involved, but only that it would “give advice” to the Japanese Red Cross Society when the latter organized and ran a registration system for those who wished to return to North Korea. As stated in the Agreement, 975 Koreans in Japan left Niigata port for North Korea by the first ship on December 14, 1959, just 60 years ago. In this way, the Diasporic Returns project started while it remained ambiguous who was responsible for protecting the human rights of those diasporic Koreans who returned to North Korea.

Koreans that returned were so astonished to see something that was totally different from the “Paradise on Earth” that North Korea had described to them. Their wishes for areas of settlement and choice in occupations did not come true. The provided food was much simpler than the food they had enjoyed in Japan. The provisions were beyond comparison and clearly insufficient. In particular, returnees were under surveillance as those who might bring about “distorted discipline and disorder” based on Japanese capitalism, and that North Korea needed to protect and enhance their socialist system centered on “Juche” (self-reliance) philosophy.

In North Korea, people were classified into several ranks according to their loyalty to Kim Il-sung. The returnees were classified as “Hostile” or “Unsettling” classes and were under surveillance. North Korean discriminatory sentiments against the returnees were widespread. Japanese returnees, in particular, became the target of bullying because of the historical resentments against Japanese colonial rule. The returnees who came to know the real picture of North Korea sent letters, written in ways that North Koreans could not decipher their meaning, to their families still in Japan, who were to return to North Korea shortly afterwards in order to prevent them from returning. This is how the problem began where families were divided between the two countries of Japan and North Korea.

The Story of Eiko Kawasaki, a Diasporic Korean in Japan

Ms. Eiko Kawasaki, Chair of Action for Korea United Japan, was born in Kyoto, Japan in 1942 as the second generation of diasporic Koreans. When she was 17 years old in Chosun High School, which was sponsored by the General Association of Korean Residents in Japan, she became interested in socialism which was prevailing in Japan as a progressive thought at that time even though she was against the personality cult for Kim Il-sung. She persuaded her parents and school teachers, and decided to return to North Korea at first alone, and left Japan at Niigata port.

Ms. Eiko Kawasaki, Chair of Action for Korea United Japan, was born in Kyoto, Japan in 1942 as the second generation of diasporic Koreans. When she was 17 years old in Chosun High School, which was sponsored by the General Association of Korean Residents in Japan, she became interested in socialism which was prevailing in Japan as a progressive thought at that time even though she was against the personality cult for Kim Il-sung. She persuaded her parents and school teachers, and decided to return to North Korea at first alone, and left Japan at Niigata port.

When the ship drew closer to Chongjin port in North Korea, she moved to the stem of the ship with the two senior boys she was traveling with in order to watch the ship dock at the port. Another senior boy who had returned to North Korea earlier shouted repeatedly to them,

“Three young guys – never get off the ship! Instead, go back to Japan without getting off the ship!”

She felt uneasy when she met thousands of local people who gathered in order to welcome them.

One week later, when she was called in for an “emergency circumstance,” a policeman explained with a grim look, “A buster pulled down a holy picture that praised the achievement of our leader Kim Il-sung, and trod it down under foot.” He explained that the young man was instructed to learn the greatness of Kim Ilu-sung. But she never saw him again. The returnees were sent, in reality, regardless of their wills, to local districts with coal mines, metalliferous mines, forestry industries, and agriculture sectors, industries that needed to make up for loss of labor from the Korean war. She was living in a cluster housing where one day she heard an argument of another family blaming those who first advocated joining in the Diasporic Returns project.

Some returnees wrote letters to Japanese families and relatives requesting economic support and managed to get provisions from Japan, Ms. Kawasaki witnessed. But others who did not have any relatives in Japan suffered a lot, living much poorer lives than North Koreans. Since her parents were to return to North Korea one year later than she, she wrote a letter saying “If my (infant) brother becomes married, come here with his wife.” In this way, she wrote a letter in a way that North Koreans could not understand her meaning, and her implicit letter managed to keep her parents from coming over to North Korea.

Ms. Kawasaki witnessed that many returnees got ill because of psychotic disorders, and some of them committed suicide. But since those who committed suicide were regarded as rebellious persons against the government and the rest of the family members could be sent to concentration camps, she explained, the returnees did not, in reality, have even freedom to commit suicide. She made up her mind to devote herself to maintaining her life by practicing “See no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil,” in other words, turning a blind eye. She thus managed to graduate from high school and study engineering at a university in North Korea.

However, Ms. Kawasaki could not forget about one particular tragedy regarding a Japanese wife, her friend. At a job site for road construction, her friend was always criticized severely for the slightest mistakes because of the resentments North Koreans had toward the Japanese. So, her friend kept working even when she was ill because she feared that she would get teased later, and as a result, she breathed her last breath while sitting on the job site.

Defecting from North Korea back to Japan

Ms. Kawasaki finally escaped from North Korea in 2003. One of her daughters and two grandchildren were also able to escape from North Korea. But her four other children are still left in North Korea. Four days after she went back to Japan in August 2004, her father passed away. She had lived with her mother for two years until her mother passed away at her bedside.

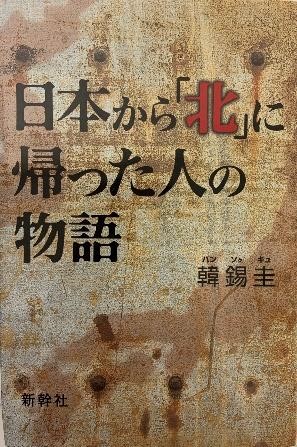

A book written by Eiko Kawasaki

She wrote a book “Stories of People who Returned to North Korea from Japan” under a Korean pen name of “Han Seok-kyu” and moved up to Tokyo for the publication. Ms. Kawasaki has never met her children left in North Korea for the past 15 years, so her family is a typical separated family. She shared,

“When I met with some leader who mentioned that we need to solve the Korean peninsula issue slowly, I argued that we need to hurry up. I want our next generations to see the unified Korean peninsula. Our generation must solve the problem.”

As a primary victim of the violation of human rights by North Korea, she is taking tireless actions every day for a day when North Korea becomes an internationally trustworthy country and when North and South Korea are unified based on freedom and democracy.

Turning a Tragedy into a Life of Activism

Ms. Kawasaki and eleven other people submitted a plea to the Japan Federation of Bar Association Human Rights Committee in January 2015 for a remedy for the gross human rights violations, thus accusing organizations engaged in the Diasporic Returns project of violating human rights and crimes against humanity. Those organizations included both the governments of Japan and North Korea, the Red Cross Society in both countries, and the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC).

In February 2018, she filed a damage suit with the Tokyo District Court for about 4 million dollars against North Korea, claiming that North Korea disguised itself as a “Paradise on Earth” and drove many diasporic Koreans in Japan to return, all the while not providing enough food to returnees, persecuting them and violating their fundamental human rights when they showed attitudes of defiance.

North Korea needs to prove that it respects human dignity and protects fundamental human rights. That is the first step for North Korea to join the international society, and it will lead to the peaceful unification of the Korean peninsula, providing peace and human rights for those living in fear and captivity.